Deadly Marine Life: The Great White Shark

Of the world’s 400 shark species, Australia is home to a whopping 170 of them.

On top of that, our waters are host to the 12 shark species that are renowned for unprovoked attacks on humans, including the 3 species that have been responsible for fatal attacks in the past 20 years – the Bull shark, the Tiger shark, and the Great white shark.

The Great white shark, as well as being the largest predatory fish in the world, is arguably the most well-known, due to its starring role in Steven Spielberg’s acclaimed horror film, Jaws (1975).

Jaws struck fear into the hearts of many and painted the Great white shark as a mindless killing machine hellbent on attacking any human that dared enter the ocean.

But is that the reality? Continue reading for an in-depth understanding of the behaviour and characteristics of the Great white shark and the first aid procedures for preventing and treating shark attacks.

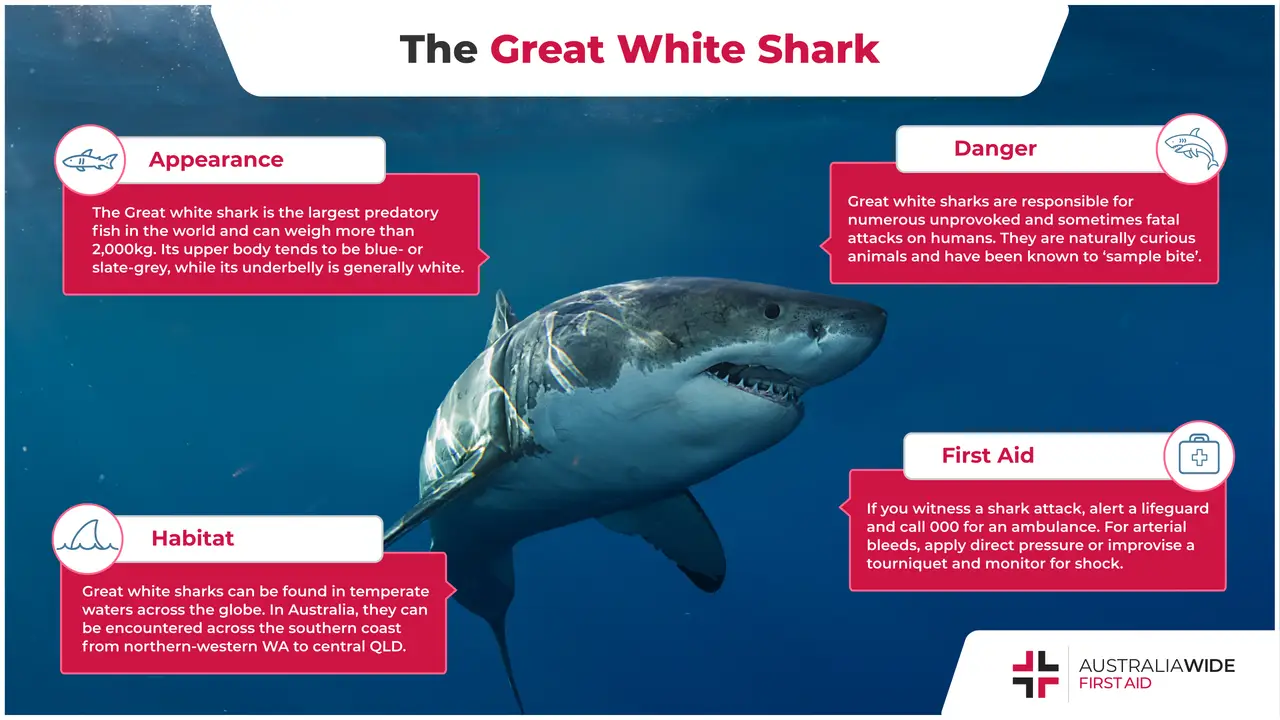

The Great white shark, or Carcharodon carcharias, is the largest predatory fish in the world. They generally average 15 ft (roughly 4.5 m) in length and weigh between 680 and 1,800 kg, though some specimens have exceeded 20 ft (roughly 6 m) and more than 2,270 kg.

Their upper bodies tend to be blue- or slate-grey in colour, which helps them blend into the rocky coastal sea floor when viewed from above. They are so named because of their white underbellies, which allow them to blend in with the sunlight when viewed from below.

Their body is shaped like a blunt torpedo, and they have a strong, crescent-shaped tail that can propel them through the water at speeds of up to 50 km per hour.

Great white sharks can be found in temperate waters across the globe, though they are frequently centred in temperate coastal waters that have plenty of fishes and marine mammals.

For this reason, they are relatively common off the coasts of Chile, New Zealand, southern Africa, northern Japan, and the north-eastern and western United States.

In Australia, they can be encountered from the Montebello Islands in north-western Western Australia and across the southern coast to at least as far north as central Queensland, including Tasmanian waters.

Great white sharks generally live in the upper part of the ocean and close to shore, where sunlight and prey are in abundance.

In their infancy, Great white sharks tend to feed on fishes and other sharks. When they reach adulthood, however, their diet can grow to encompass seals, dolphins, sea turtles, sea lions, and even small whales.

Great white sharks are excellent predators. Their mouths can house up to 300 serrated and sharply pointed teeth at any one time. And in conjunction with having an exceptional sense of small, Great white sharks have organs that can detect the miniscule electromagnetic fields generated by animals.

When attacking their prey, Great white sharks generally use their powerful tail to ambush the animal and inflict a single fatal bite. Sometimes, this rush can be so great as to propel the shark out of the water. They then wait for their prey to die, a method of attack that is sometimes called the ‘bite and spit’.

Great white sharks are viviparous and so give birth to litters of between 2 to 10 live pups after an estimated gestation period of 12 months. At their time of birth, pups are generally 1.5 m in length.

Though there is no reliable population data for Great white sharks, it is generally agreed that their numbers are dropping sharply. In fact, their conservation status is currently listed as Vulnerable, which is only one step away from Endangered.

As well as being hunted for their teeth and fins, Great white sharks are often hunted as trophies for sport fishing. Likewise, they are often caught inadvertently in shark nets and by commercial fisheries. As a top predator, Great white sharks serve a vital function in balancing the populations of different marine mammals. Their continued depletion could subsequently have a devastating impact on the food chain.

Great white sharks are responsible for numerous unprovoked and sometimes fatal attacks on humans.

However, it is important to remember that these attacks are rare.

And unlike the narrative peddled in Jaws, many researchers believe that Great white attacks on humans stem from the shark’s curiosity, rather than an insatiable desire for human blood. Great white sharks are naturally curious animals and have been known to ‘sample bite’ humans before retreating. Many researchers also attribute fatal attacks to cases of mistaken identity – that is, when the shark mistakes the human for a seal, their preferred prey.

There are several ways you can reduce your risk of a shark attack:

More tips for avoiding and surviving a shark attack can be found in our article on Shark Attack First Aid.

If you witness a shark attack, alert a lifeguard, make sure others are warned, and call Triple Zero (000) for an ambulance.

If you need to rescue the person from the water, use a boat as soon as it is safe to do so. Do not put yourself at risk if no lifeguard or boat are available.

Then:

A tourniquet is a tight band that can help stop or severely reduce the flow of blood around a wound. You can improvise a tourniquet using a surfboard leg rope, a belt with a buckle, or something similar.

Make sure to wrap the tourniquet high up the limb, tightly and horizontally.

More information about providing first aid in the event of a shark attack can be found in our Resource Library.

With over 25,000 km of coastline, Australia is no stranger to shark attacks. Not only do we have the highest diversity of shark species in the world, we are home to the 3 shark species that have been responsible for fatal attacks in the past 20 years – the Bull shark, the Tiger shark, and the Great white shark.

It is important to remember, however, that shark attacks are relatively rare – in fact, you are more likely to die from a hornet, wasp, or bee sting than from a shark attack.

As we have seen today, Great white sharks are not as mindless as their Jaws counterpart. Though they certainly are a formidable predator, with their large size and highly serrated teeth, Great white sharks are more likely to bite humans out of curiosity than menace.

Luckily, there are several ways you can reduce your risk of running into a Great white shark. There are also multiple avenues for fending off a Great white shark and treating any injuries you may sustain during an attack.

To develop even more knowledge and skills to keep yourself safe in the water this summer, book a First Aid course with Australia Wide First Aid today.

March 11, 2025

Darwin, the tropical capital of Australia’s Northern Territory, is home to a rich diversity of wildlife - including an impressive array of spiders. From the sprawling webs of golden orb-weavers to the cryptic camouflage of trapdoor spiders, these arachnids play a vital role in the local ecosystem. While some may inspire fear, the majority are harmless and even beneficial, helping to control insect populations.

September 4, 2024

Cat bites, while often underestimated, can lead to serious health complications if not treated promptly and properly. Cats' mouths harbour a variety of bacteria that can cause infections in humans.

April 1, 2024

Encounters with wildlife can often be thrilling, but when it comes to the creature known as the drop bear, the experience can quickly turn dangerous. A sharp increase in recent attacks prompts the need for understanding proper first aid procedures in case of an attack.